Markets are full of surprises. We have seen plenty over past the week, and even more over the past few years. Should we be surprised though? We discuss three principles to help improve portfolio construction to help deal with the inevitable surprises that will occur as investors.

Market Microscope

Use Principles to Guide your Process

“You have power over your mind, not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.”

-Marcus Aurelius

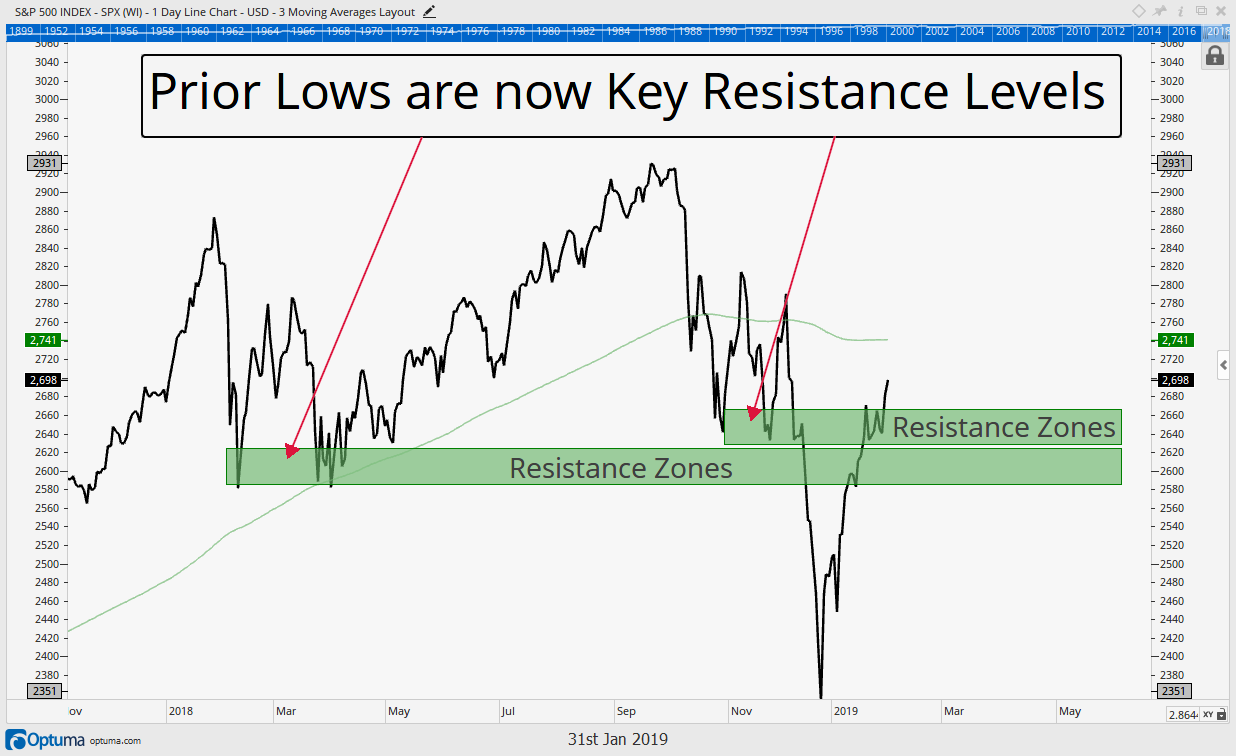

The S&P 500 broke to new all-time highs over the past few weeks, and as we wrote two weeks ago in “Yes, Dear”, new all-time highs should be considered bullish.

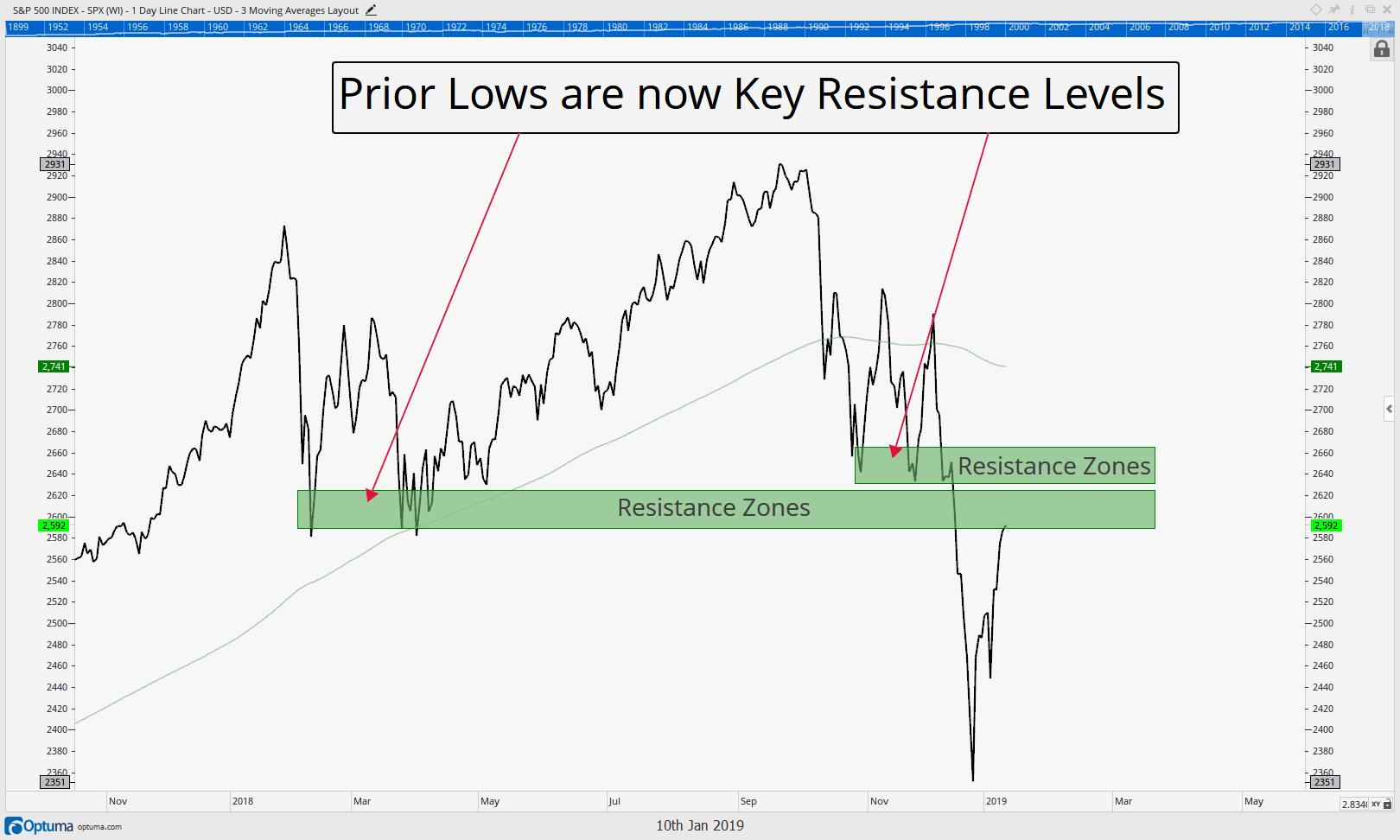

However, last weekend’s news that trade tensions with China were heating up again cleared the way for increased selling pressure. Some would say this was a surprise, but is it really?

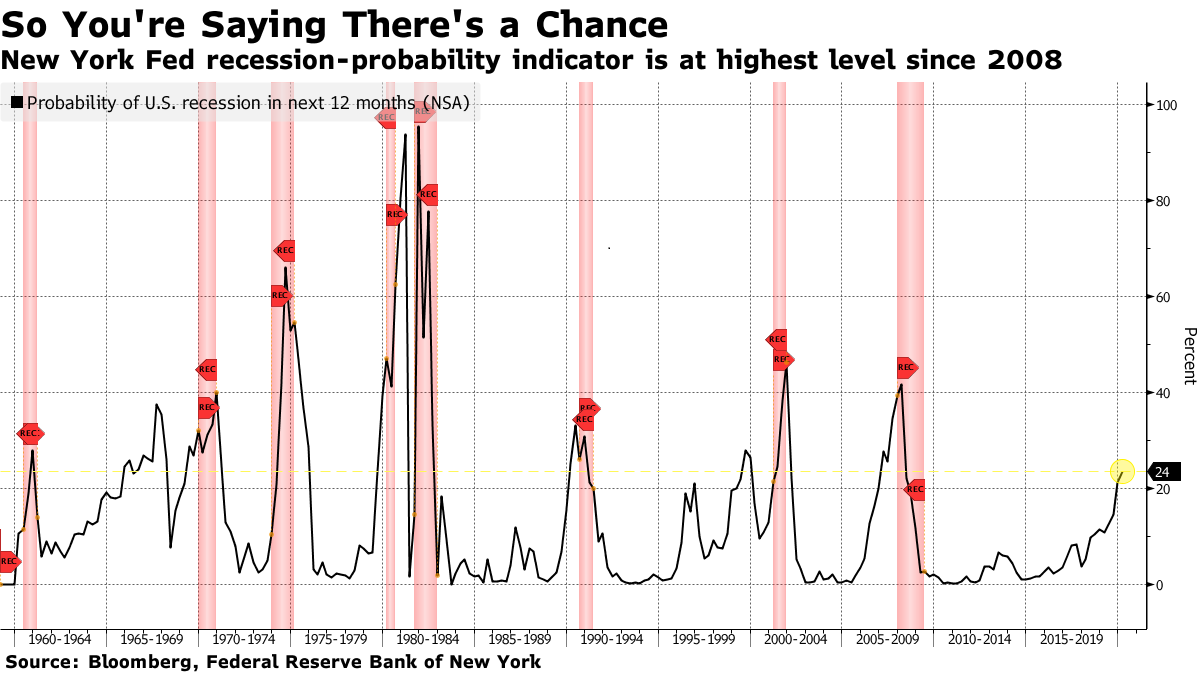

Should we be surprised that Trump is jaw-boning of the Federal Reserve to reduce rates? Should we be surprised that a trade deal is not done, given the sizes of the two respective economies?

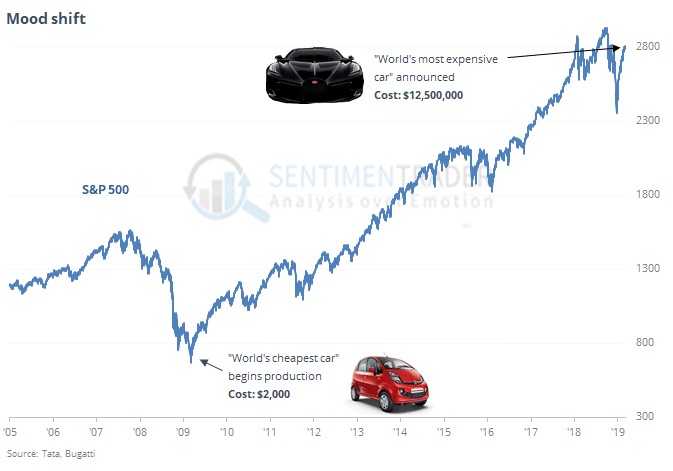

Should we be surprised that the market is taking a pause after a furious rally from the December lows? Should we be surprised that the “animal spirits” of a 10-year old bull market continue to push markets higher despite frothy valuations?

No we should not be surprised. We know better. We should EXPECT the surprise and be prepared for it, even if we don’t know what form the surprise will take.

So what are you supposed to do as an investor when faced with such surprises?

There are many answers to this question.

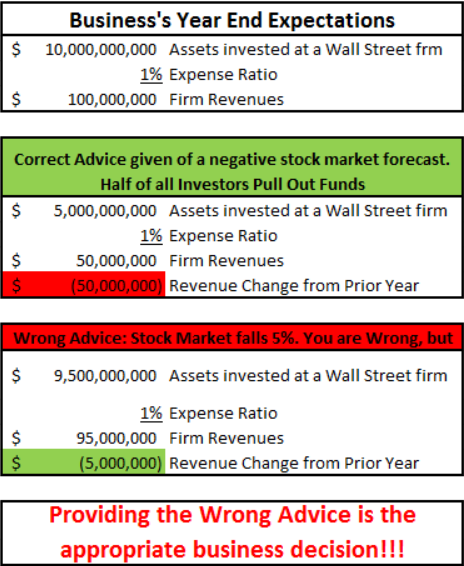

The run-of-the-mill investment advisor, including those at nearly every large investment firm, would suggest that you should just stay invested everywhere and always. They would suggest you not pay attention to the news, that you don’t open your statement when markets are volatile, that you don’t ask them tough questions about what is really happening in your investment portfolio.

The basis of this strategy is “Hope”.

You (and the advisor referenced above) hope the markets don’t fall too far. You hope you have the resources to withstand a major decline. You hope that it continues to rise like it has the past 10 years.

But what if that hope is misguided? What if the decline from last year was just a precursor of more downside to come? Or conversely, what if the market keeps going up for the next 5 years, despite this already being the longest expansion in history?

We’ve said many times that “Hope is not an investment strategy”.

In order to effectively address both downside and upside surprises, you must operate under a set of principles that guide your behavior during times of uncertainty.

And more importantly, these principles must be established and tested PRIOR to uncertain times, or else they will be abandoned when you need them most. This is why we hear of people who have sold at the bottom (or in many cases you may have been one of the people that sold at the bottom). Without governing principles, it is incredibly easy to abandon a plan. If there was even a plan at all.

Operating with a specific set of principles allows you to execute your plan with consistency, no matter what the environment may bring.

At IronBridge, we believe the following principles are essential to investment success:

- Accept reality as it is, not as you wish it to be.

- Markets are too complex to successfully predict with consistency.

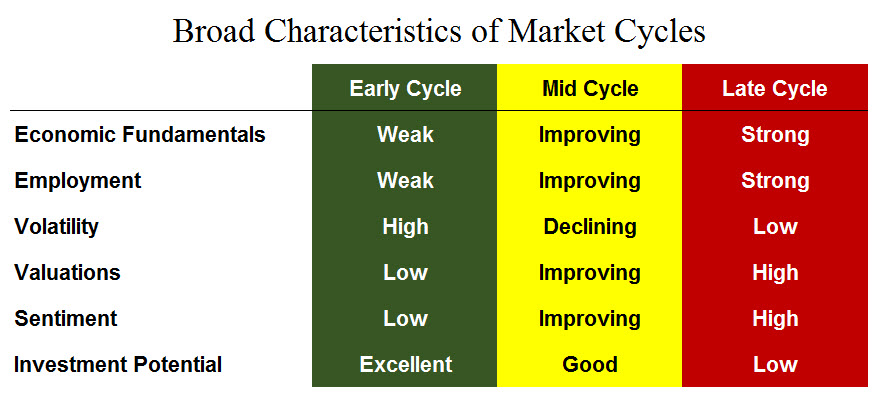

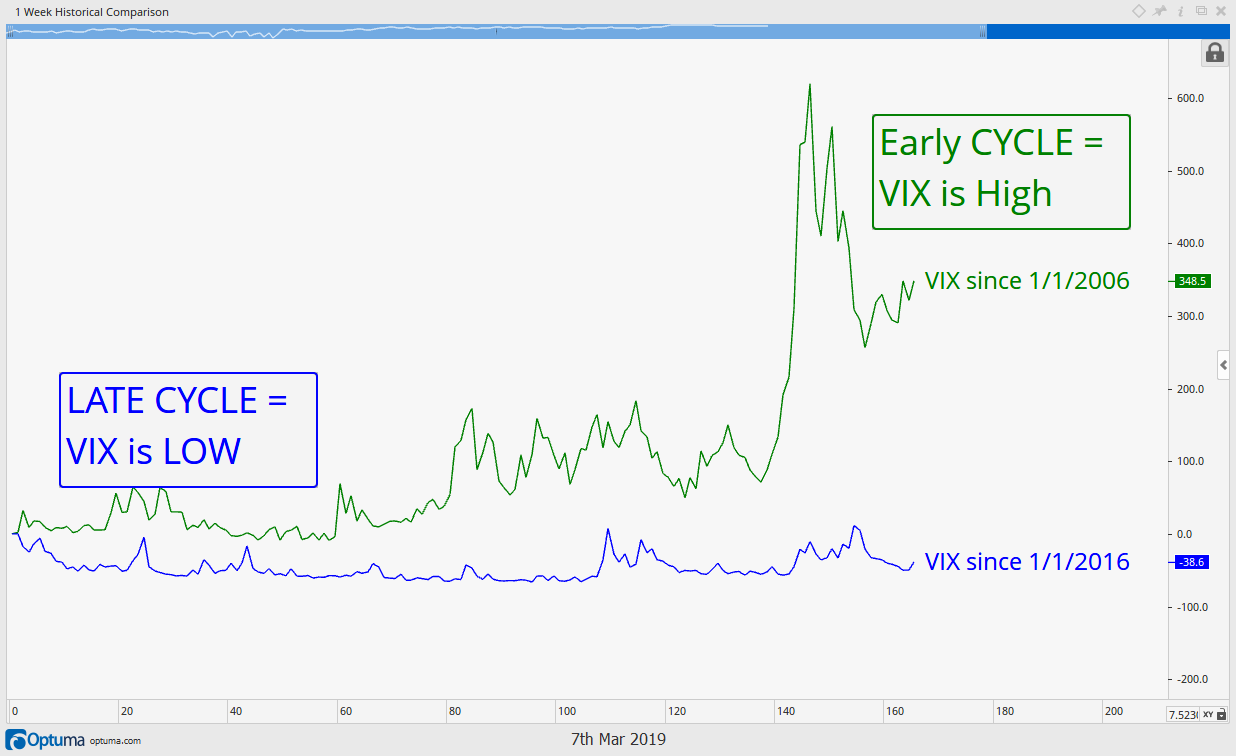

- Markets work in cycles; You must adapt to succeed.

The common theme in our principles is pretty simple: WE DON’T KNOW EVERYTHING.

And that’s okay.

As people who have been in the investment industry for decades, we realize that this goes against the fabric of what this industry has been built upon…the massive egos of mostly insecure men.

Turn on CNBC and you’ll hear these egos stating with great authority and confidence about exactly what happened in the markets today and why. Followed by someone who will state with equal confidence predicting exactly what will happen tomorrow, next week or years into the future.

Guess what…they are making it all up.

Once you can come to terms that there is more uncertainty in the future of the markets than what you think, you then are liberated to develop a truly effective investment strategy.

Let’s go through our principles briefly:

Principle 1: Accept Reality as It Is, not as You Wish it To Be

Principle 1: Accept Reality as It Is, not as You Wish it To Be

We won’t get to deep into the psychological and behavioral finance issues that cause us humans to project our own belief system onto the world around us. There are countless books that address these topics.

We simply need to know that we are predisposed to certain subconscious flaws when it comes to investing. It’s okay, we’re human. If we can recognize how certain flaws may negatively affect outcomes, then we can include in our investment process tools which serve to minimize these flaws.

These flaws cause us to view things in a way that is not truly objective. We all have prior experiences that we bring to our current view of markets. Some people have been burned too many times to invest in stocks. Others have been successful and have no problem holding through periods of volatility. There is nothing wrong with either view, as long as we can acknowledge and recognize the lens through which we see the world.

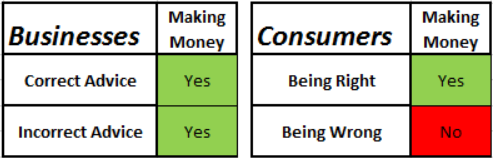

The single biggest flaw is ego. We as humans want to be correct. We want to be right. We want to be able to believe that we have insights that others don’t.

Accepting reality delivers a blow to our ego. It causes us to face the fact that we might be wrong. And being wrong implies being ineffective.

So most investment professionals focus on trying to be right. And it is only natural that as someone who uses an investment professional, you want them to be right just as badly. The fact is, markets go up roughly 80% of the time. (At least that has been the case for the professional lives of anyone in the industry today…there are plenty of instances where financial markets languished for decades, but that is for another day).

Accepting reality can be difficult, but it is absolutely critical when it comes to risk management.

Many times our process has identified a stock that meets all the proper criteria for inclusion in a portfolio: a great company, sound fundamentals, favorable trend, solid growth potential, and excellent risk/reward metrics.

We optimistically buy this stock for clients. We can visualize the experience of sweet delight as we watch this stock rise in value for our clients.

Then it does exactly the opposite of what we think it will do.

A couple weeks later it declines and reaches our predefined exit price. If we let our ego get in the way, we would hold this stock. It met all of our criteria. It’s a well-known company with a great track record. Surely this stock will turnaround and prove that our analysis was in fact correct. “The market is wrong about this stock,” we might be inclined to say.

What should we do?

It’s not always easy to do, but we follow our process. We sell the stock and move on. Maybe it will provide another quality setup in the future that will generate profits. Maybe it bounces immediately after it is sold. But that doesn’t matter. It didn’t work. We gave it room to breathe, and identified the prudent level of capital to risk on that investment. It unfortunately didn’t grow like we thought it would, so we move on. There are thousands of stocks, why stick with one that isn’t working?

What matters is having a proven, repeatable process that you can adhere to.

Accepting reality keeps your ego out of the equation. If you don’t care about whether you are right or wrong on the direction of a stock or the market in general, you can more objectively assess and execute a successful strategy.

Principle 2: Markets are too complex to successfully predict with consistency

Principle 2: Markets are too complex to successfully predict with consistency

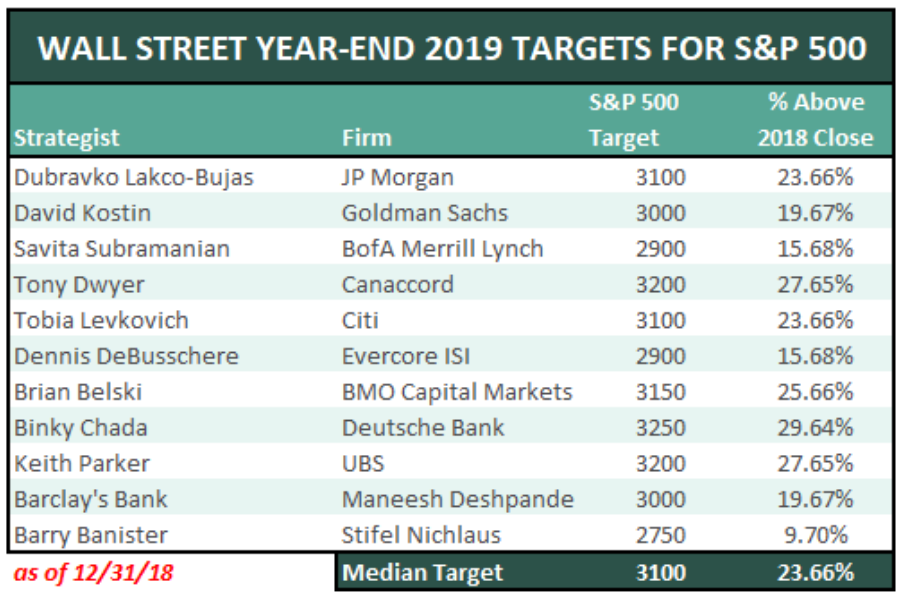

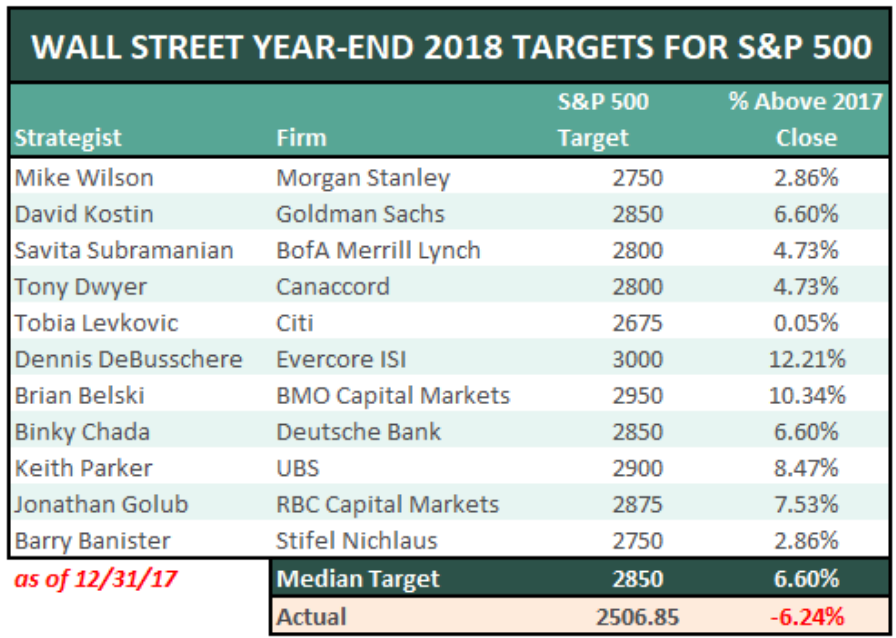

In our opinion, this is the hardest principle to fully embrace. The investment industry overwhelms us with market predictions.

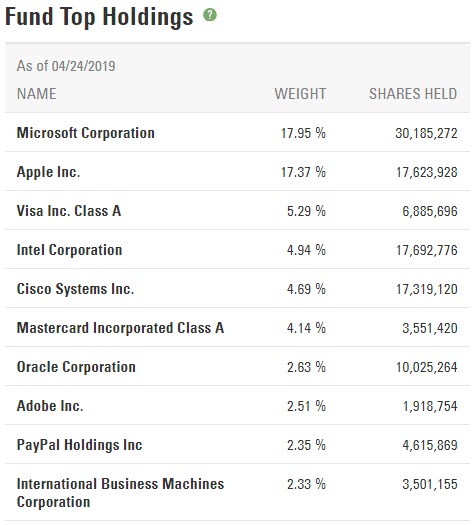

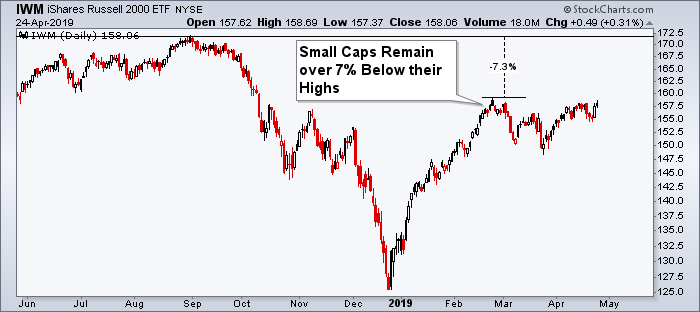

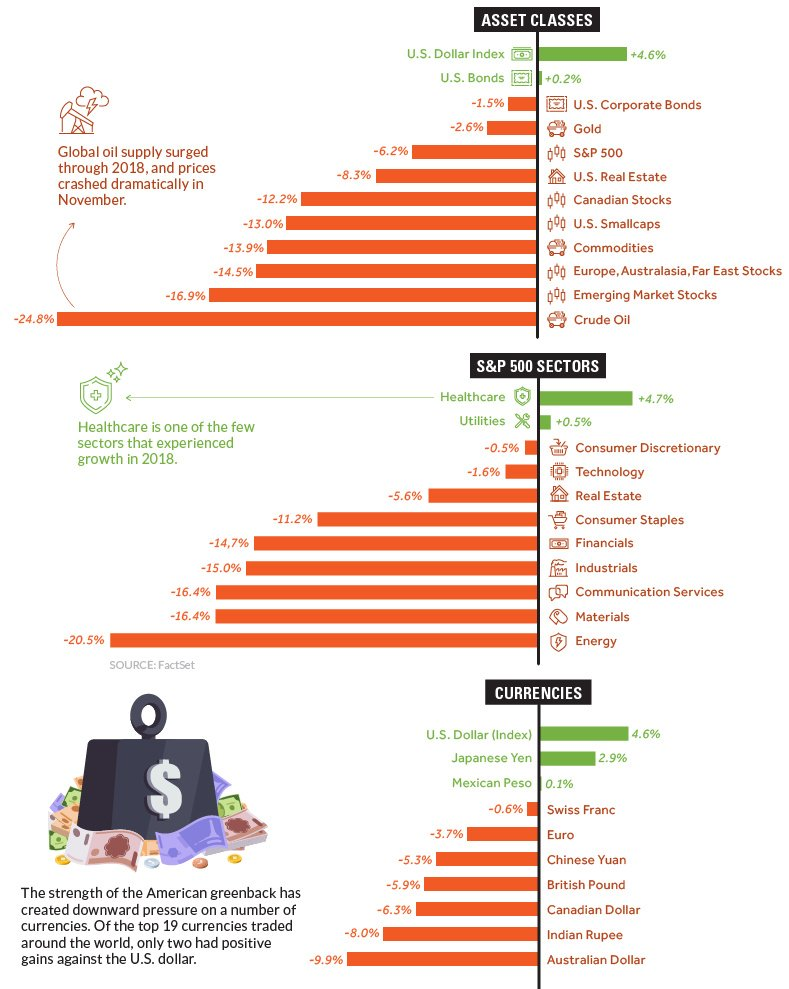

Every day we see fancy reports that discuss predictions about things. Some are obvious, like the litany of year-end predictions in January. But some of them are more subtle. Overweight international stocks, underweight small caps, even-weight bonds, etc. These inherently involve predictions about the future.

They’re everywhere. But are they useful? Are the people who make the predictions held accountable? Is there a track-record anywhere that measures these market predictions? Of course not. The marketing department wouldn’t let that happen. Nor would their legal counsel. The fact is that most predictions don’t have any better track record than a randomly selected period of time.

So if we’re not predicting, what can we do? In the past, the information we had available to us was limited. The Wall Street Journal was the internet of the day. CNBC was actually a valuable resource (imagine that).

Today we have data. Boatloads of data. We don’t need the overconfident investment gurus to guide us with their predictions or analysis.

In many ways, we have too much data. So it not only becomes a puzzle of finding data, but filtering data so that it is impactful and useful.

We believe the best way to address uncertainty is by combining data analytics and judgement based on experience.

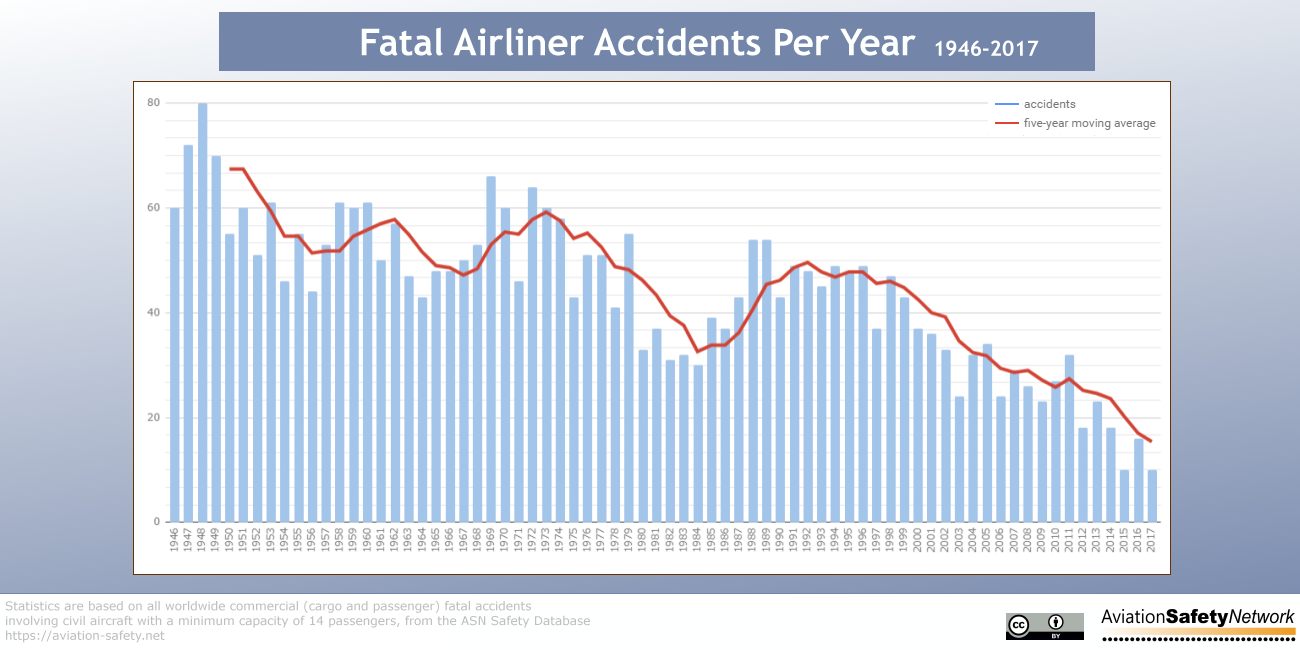

The best example of a successful integration of data and judgement can be found in aviation. The combination of an experienced pilot using the help of computers to fly a plane has resulted in a dramatic decrease in the annual rate of fatal airliner accidents, as shown in the chart below.

As we have unfortunately seen this year, when technology alone is in control, bad things can happen. Two accidents with the newest Boeing jetliner were due to the pilots’ inability to override the technology used to fly the plane.

And it backfired tragically.

While hundreds of people won’t lose their life if your portfolio falls 50%, we can still learn valuable lessons to help avoid financial disasters.

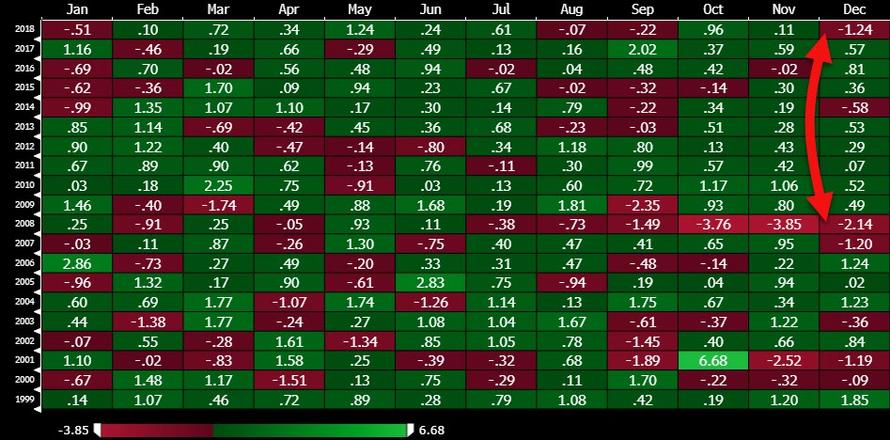

Because there is a tremendous amount of data available, there are many way to use it. In our opinion, we choose to look at a combination of fundamental data, quantitative data, and sentiment readings.

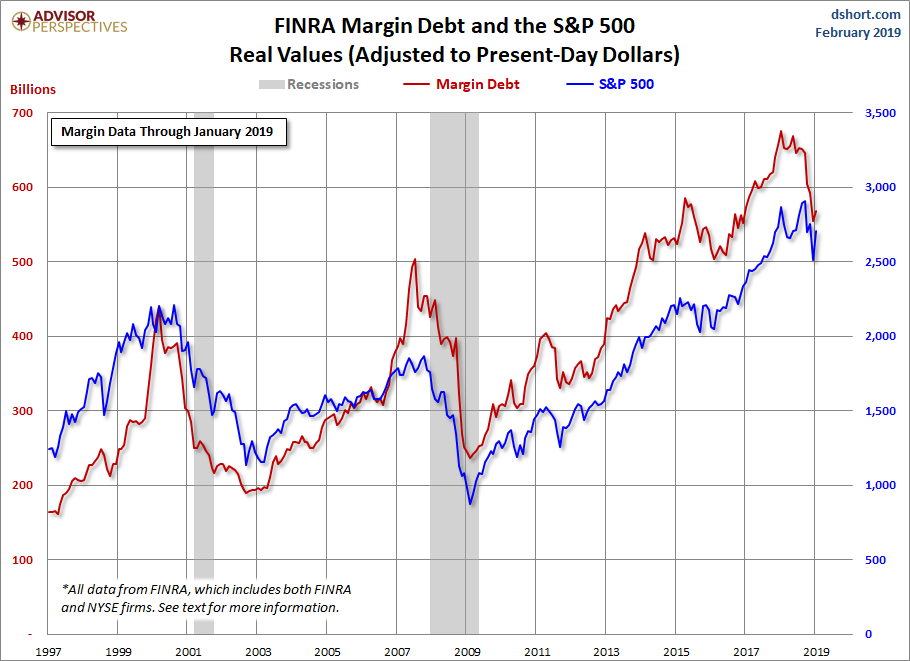

Fundamental data includes things like the economy, company earnings, employment, etc. These are the things that can give us context about the general investing environment, but are actually very poor if you’re using them to guide investing decisions.

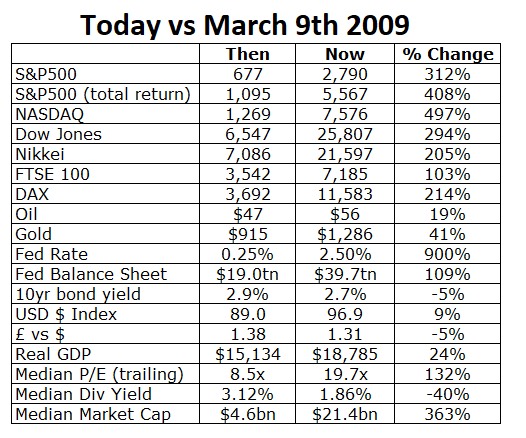

Case in point: One investing environment has a 4.5% GDP, 4% unemployment, has been growing for 5 consecutive years, with record corporate profits. The second environment has negative 5% GDP, 12% unemployment, been in a recession for 15 months, and there are companies on the verge of bankruptcy.

Which environment would you choose?

The first environment was characteristic of 2007 near the peak of the market. The second was in April 2009, one month into the longest bull market in history. The second environment, when the economy was awful, provided the best investment opportunity, while the second led to a decline of 55% in markets.

Economic data only provides context. It does not have a direct affect on markets.

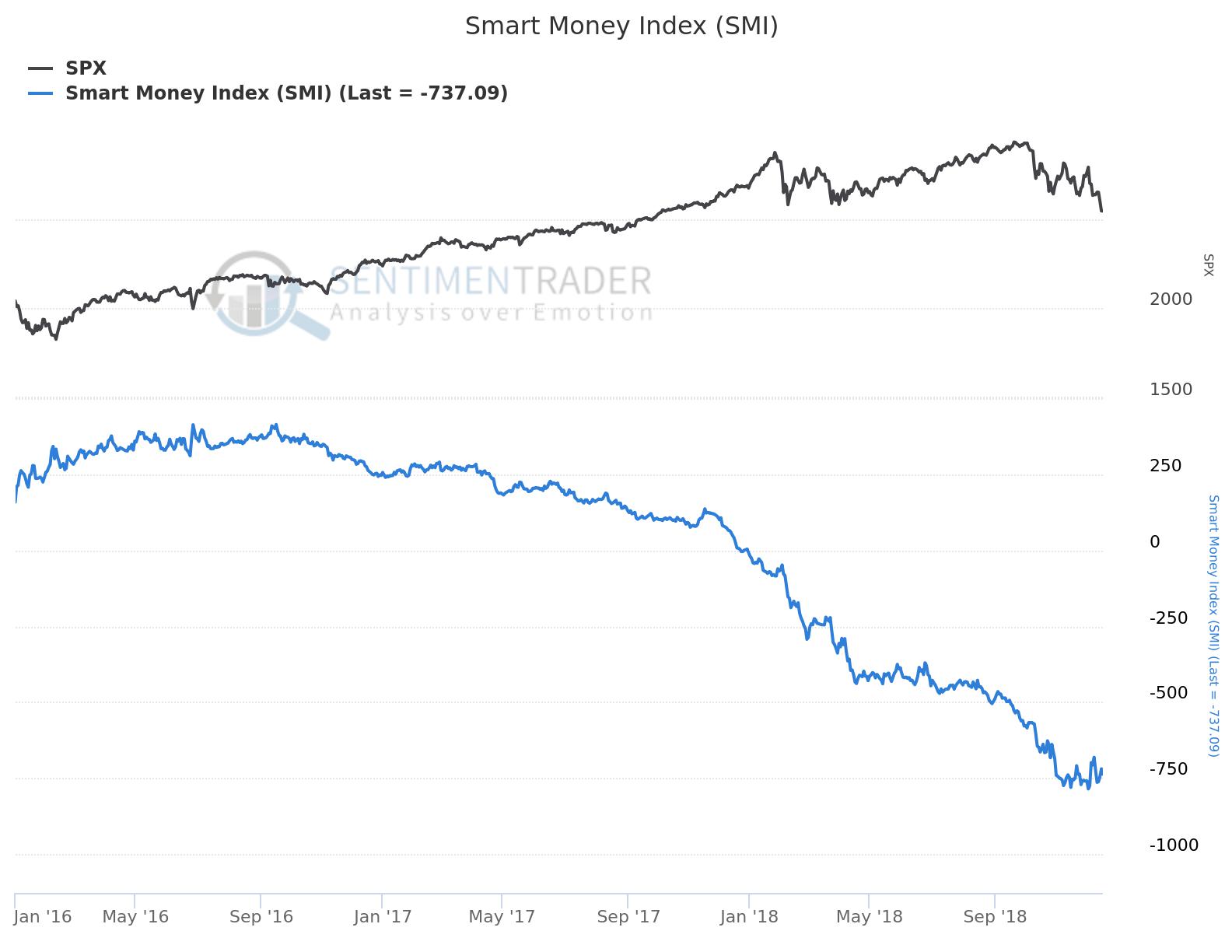

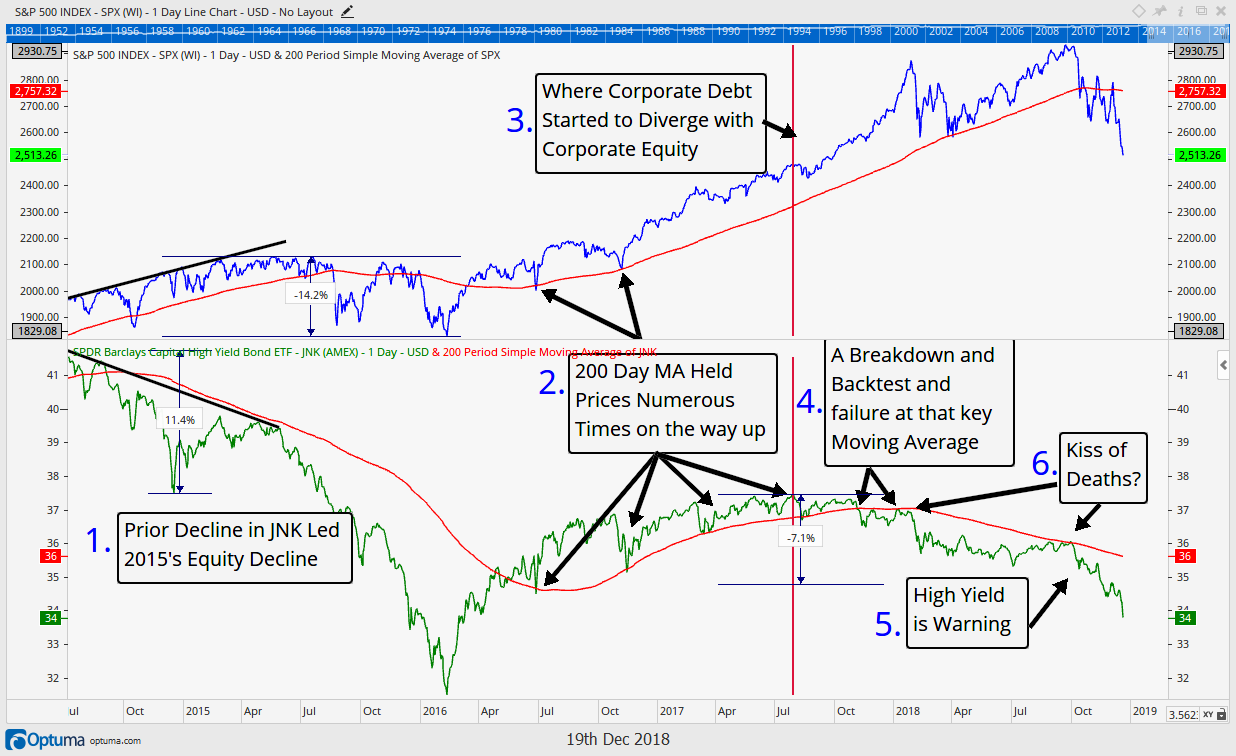

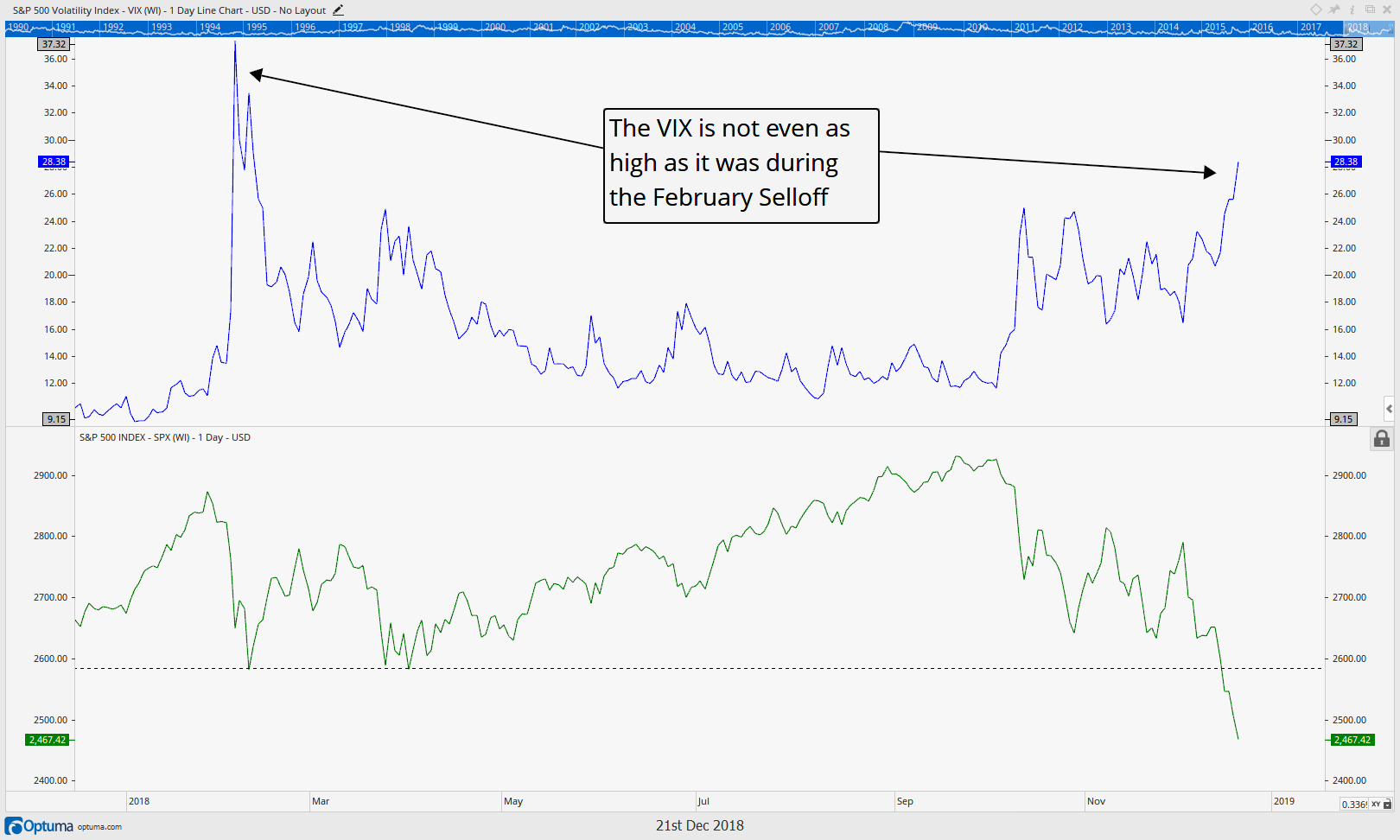

Quantitative and sentiment data has a more direct effect, because they are actual influences on market prices. Buy and Sell volume. Optimism and Pessimism of actual market participants. Put/Call ratios. Momentum and Relative Strength measures. These provide more than context…they provide actionable signals to improve risk/reward characteristics of a portfolio.

If you do feel compelled to try to predict the market, present alternatives. What are the various scenarios that could play out? Be your own devil’s advocate and your results will improve.

Principle 3: Markets work in cycles. You must adapt to succeed.

Principle 3: Markets work in cycles. You must adapt to succeed.

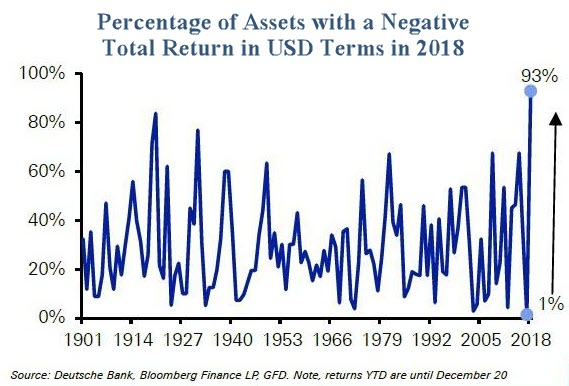

This seems obvious to us, but it is not to most. People forget about market cycles 10 years into a bull market.

This is also a difficult principle to act upon. Principle number 2 states that we can’t predict the markets, so how could we possibly adapt to a changing market cycle?

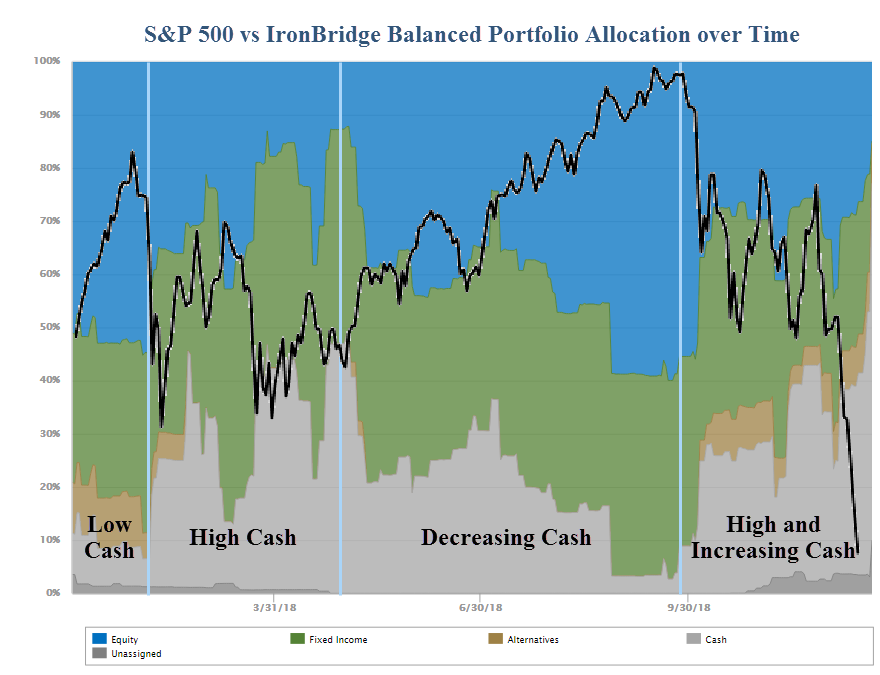

You must have a plan. Having a set of rules allows you to participate in rising markets while minimizing damage in declining ones.

We won’t dive too much into rules, as there are millions of possible combinations.

At IronBridge, some of the rules we have developed include methods to stack-rank investments based on specified criteria, performing comparative analysis among multiple asset classes, breaking down markets into various sub-components, rules around the maximum loss to take on a given position, rules that direct the entry and exit of securities, and rules around overall portfolio construction so that clients of varying financial circumstances can benefit from similar actions in portfolios.

Ultimately, the specific rules matter, but they don’t matter as much as simply having a set of rules. Once you have an established set of rules, you can back-test them and see if they would have adjusted to a changing market. You can see the maximum loss, or maximum gain. You can have data around what your strategy would have actually done. This will provide confidence in implementing that strategy in various market environments.

What these principles serve to do is shift control back into your hands. You don’t have to be subject to the whims of global politics. You don’t have to subject your hard earned capital to large potential losses. You can expose your capital and know the worst case scenario, while shifting the odds in your favor that you will experience much more of the good and best-case scenarios.

Surprises will forever be a part of investing. Accept that they will occur, plan your actions beforehand, and execute your strategy with rigor. You can shift control from outside events to your own actions. Doing so will help you succeed.

Invest wisely.

Our clients have unique and meaningful goals.

We help clients achieve those goals through forward-thinking portfolios, principled advice, a deep understanding of financial markets, and an innovative fee structure.

Contact us for a Consultation.

Neither the information provided nor any opinion expressed constitutes a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security. The investments and investment strategies identified herein may not be suitable for all investors. The appropriateness of a particular investment will depend upon an investor’s individual circumstances and objectives. *The information contained herein has been obtained from sources that are believed to be reliable. However, IronBridge does not independently verify the accuracy of this information and makes no representations as to its accuracy or completeness. Disclaimer This presentation is for informational purposes only. All opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of this communication and are subject to change without notice. > Neither the information provided nor any opinion expressed constitutes a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security. The investments and investment strategies identified herein may not be suitable for all investors. The appropriateness of a particular investment will depend upon an investor’s individual circumstances and objectives. *The information contained herein has been obtained from sources that are believed to be reliable. However, IronBridge does not independently verify the accuracy of this information and makes no representations as to its accuracy or completeness.